The problem with de-alerting nuclear weapons

Many people consider the de-alerting of nuclear weapons to be a positive step towards reducing the likelihood of nuclear war, however, despite its advantages, many fail to address the inherent issues that prevent this concept from becoming a reality.

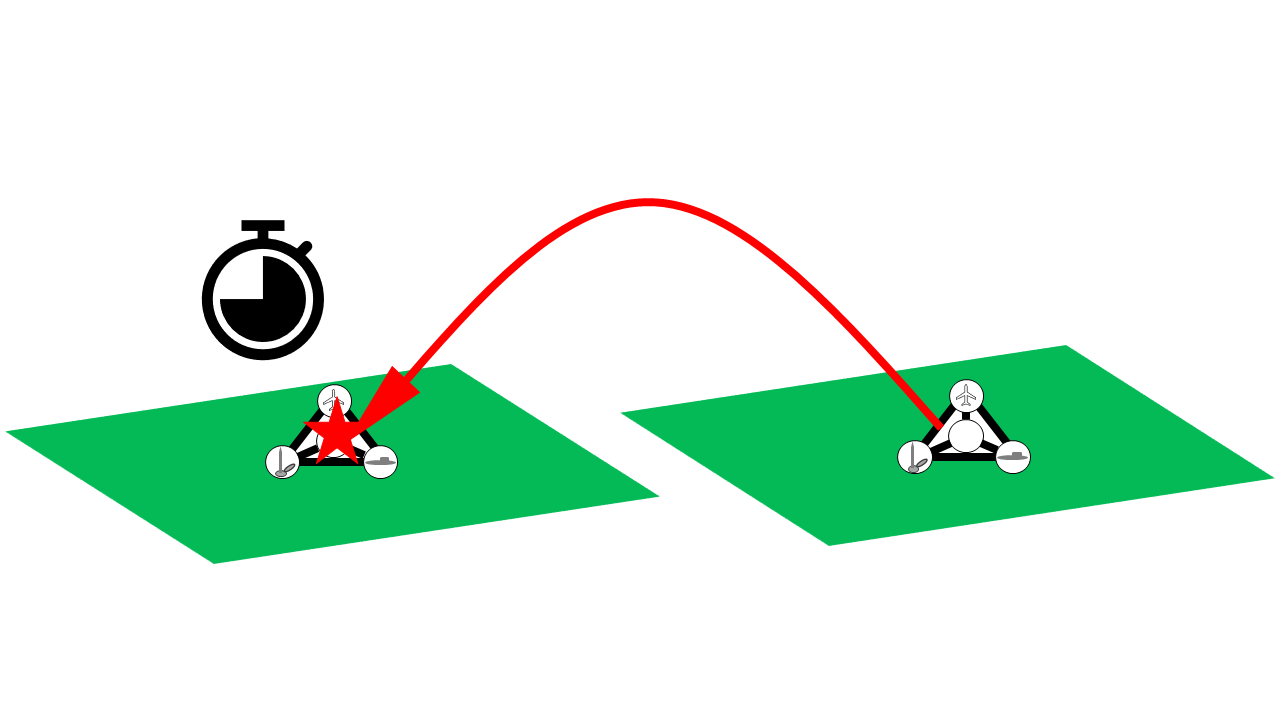

Let’s consider the practicality of de alerting the various parts of the nuclear triad.

Bombers can be de alerted by keeping them unfuelled and

keeping their weapons locked inside nearby weapons storage facilities, this is

something an adversary could verify using near real time surveillance

satellites.

Requiring aircraft to be both fuelled and armed before take-off would take many hours and be readily detectible to an adversary.

Silo based ICBMs can be de alerted by placing large, heavy

objects over their lids, to remove all of the objects may take days.

Mobile ICBMs could have their warheads removed to be stored

in secure facilities at their bases again possibly requiring days for all

warheads to be re-install.

Again, both of these could be verified by near real time satellite imagery.

Submarine based missiles could be de alerted by keeping

submarines in port unloaded with their missile tube lids open, to be verified

by near real time satellite imagery.

They could also be deployed at sea, with ballasts installed along with the MIRV warheads of the missiles to reduce their range and patrol outside the ranges of the missiles, to be verified by broadcasting their approximate location at regular intervals.

The problem with all of these de-alerting techniques is they significantly degrade the survivability of the deterrent force.

Even if we assume that both sides trust each other enough to de alert their forces, if one side becomes suspicious of the other sides activities,

it will try to re alert its forces in response,

creating an incentive for the other side to re-alert its own forces.

This creates a dangerous race to alert where the chance of unintentional nuclear war is significantly increased.

For de alerting to be sustainable both sides must be

confident that their ability to respond to an attack will remain intact, this

is not possible with full de-alerting so a proportion of the nuclear forces will

remain on high alert.

For example, land-based ICBMs in a state of possible high alert, and submarines with unknown positions at sea cannot possibly be verified as on or off alert.

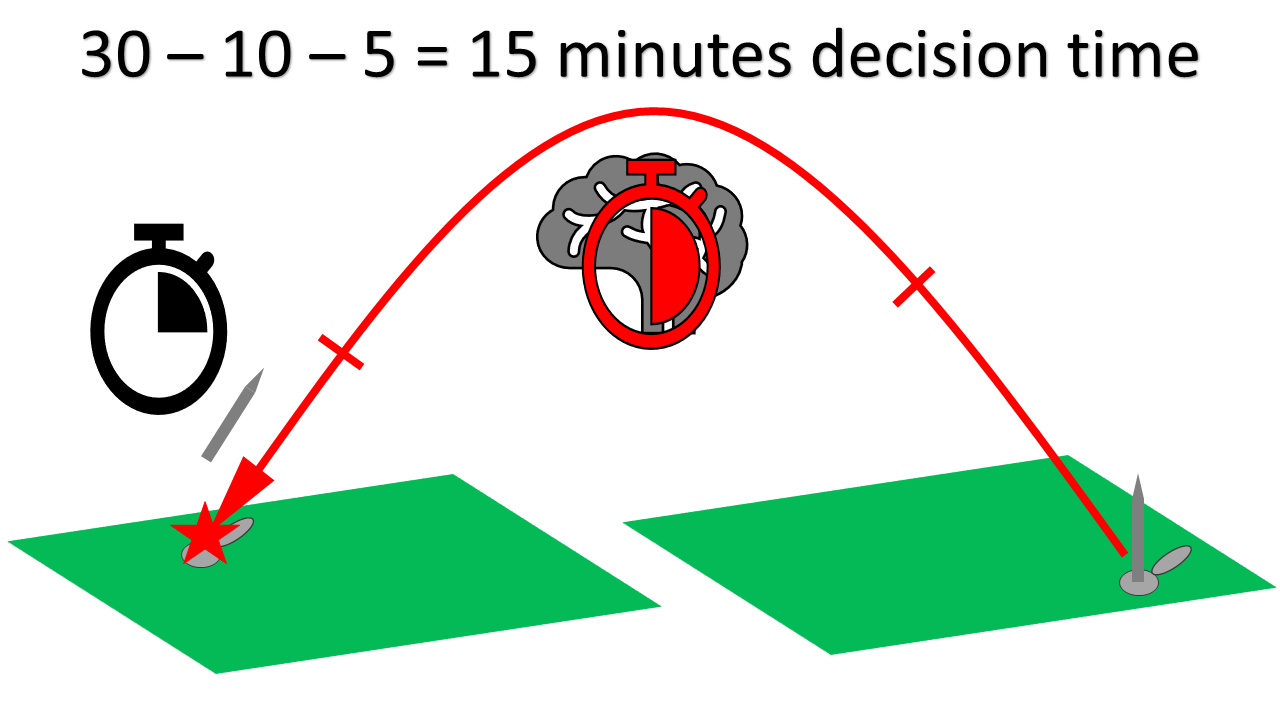

This raises another point, that reducing the alert rate of a

system does not necessarily increase decision time.

Let’s consider a silo-based ICBM partially de-alerted to a 14-minute alert rate vs a 4-minute alert rate, where alert rate is the time taken from the order being given to the missile being launched, allowing 1 minute for the missile to fly far enough away from its silo to survive an attack.

We will also assume the attack is from an enemy ICBM with a time of flight of 30 minutes, where it takes 10 minutes from missile launch, to detect the launch, gather satellite and radar information, and relay the information to the head of state.

For the 14-minute alert rate, the missile must be launched no later than 15 minutes before the projected time of impact for the missile to survive, giving 30 minutes minus ten minutes minus 15 minutes equals 5 minutes decision time.

For the 4-minute alert rate, the missile must be launched no

later than 5 minutes before the projected time of impact for the missile to

survive, giving 30 minutes minus 10 minutes minus 5 minutes equals 15 minutes

decision time.

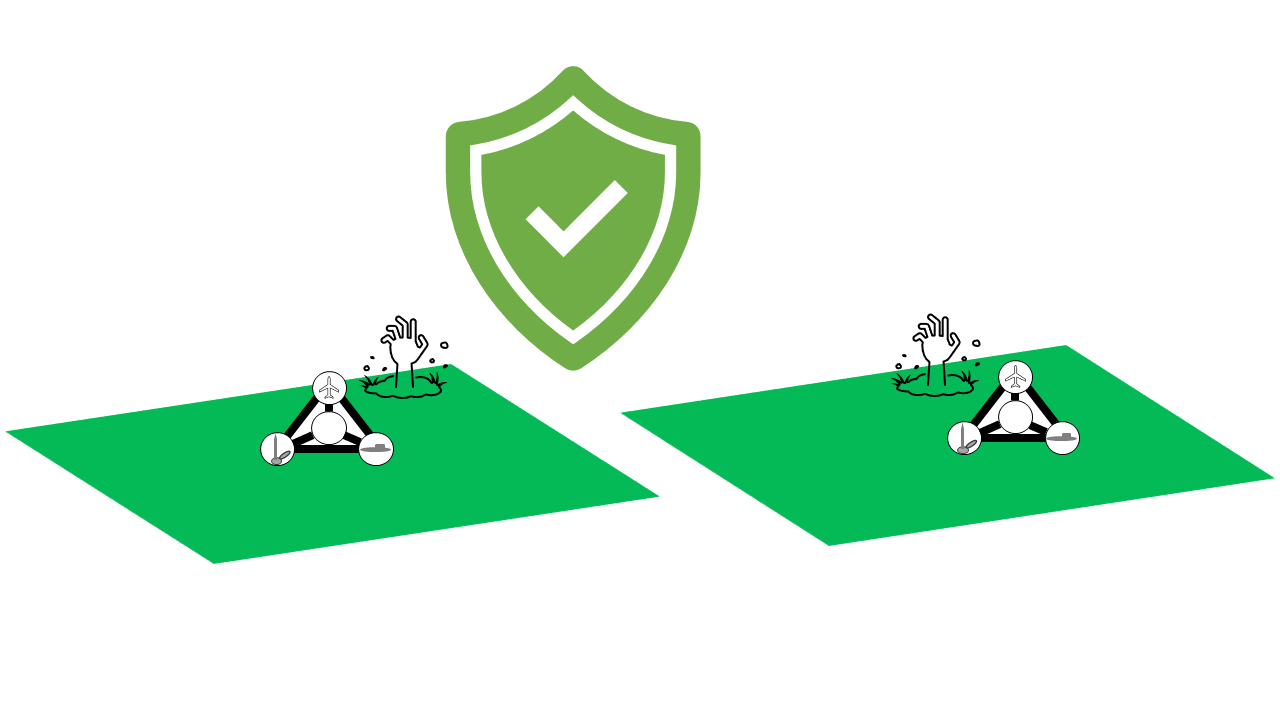

Ultimately the only way to remove the incentive for either side to be pressured into making a quick decision of whether or not they should launch a response to an unconfirmed attack is to make their deterrent force as survivable as possible.

Therefore, it doesn’t matter what the alert rate is or if they launch a response before an attack arrives, or after the attack has taken place.

As long as there are sufficient checks and balances in place to prevent a wrongful launch order and that the launch procedure contains sufficient order verification, nuclear weapons on high alert do not necessarily pose a significant risk.

Comments

Post a Comment